The Problem of Panhandling

This guide addresses the problem of panhandling.† It also covers nearly equivalent conduct in which, in exchange for donations, people perform nominal labor such as squeegeeing (cleaning) the windshields of cars stopped in traffic, holding car doors open, saving parking spaces, guarding parked cars, buying subway tokens, and carrying luggage or groceries.

† "Panhandling," a common term in the United States, is more often referred to as "begging" elsewhere, or occasionally, as "cadging." "Panhandlers" are variously referred to as "beggars," "vagrants," "vagabonds," "mendicants," or "cadgers." The term "panhandling" derives either from the impression created by someone holding out his or her hand (as a pan's handle sticks out from the pan) or from the image of someone using a pan to collect money (as gold miners in the American West used pans to sift for gold).

The guide begins by describing the panhandling problem and reviewing factors that contribute to it. It then identifies a series of questions that might help you in analyzing your local problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem, and what is known about those responses from evaluative research and police practice.

Generally, there are two types of panhandling: passive and aggressive. Passive panhandling is soliciting without threat or menace, often without any words exchanged at all—just a cup or a hand held out. Aggressive panhandling is soliciting coercively, with actual or implied threats, or menacing actions. If a panhandler uses physical force or extremely aggressive actions, the panhandling may constitute robbery.

Isolated incidents of passive panhandling are usually a low police priority.1 In many jurisdictions, panhandling is not even illegal. Even where it is illegal, police usually tolerate passive panhandling, for both legal and practical reasons.2 Courts in some jurisdictions have ruled that passive panhandling is constitutionally protected activity. Police can reasonably conclude that, absent citizen complaints, their time is better spent addressing more serious problems. Whether panhandling and other forms of street disorder cause or contribute to more serious crime—the broken windows thesis—is hotly debated, but the debate is as yet unsettled.3 Panhandling becomes a higher police priority when it becomes aggressive or so pervasive that its cumulative effect, even when done passively, is to make passersby apprehensive.4 Panhandling is of greater concern to merchants who worry that their customers will be discouraged from patronizing their business. Merchants are most likely to call police when panhandling disrupts their commerce.5, †

† Business owners who work on site are most likely to call police. Employees, especially younger employees, are less likely to do so because they have less at stake if panhandling disrupts business (Goldstein 1993).

Police must also be concerned with the welfare of panhandlers who are vulnerable to physical and verbal assault by other panhandlers, street robbers‡ or passersby who react violently to being panhandled.6 Panhandlers often claim certain spots as their own territory, and disputes and fights over territory are not uncommon.7

‡ In one study, 50 percent of panhandlers claimed to have been mugged within the past year (Goldstein 1993).

Broadly speaking, public policy perspectives on panhandling are of two types—the sympathetic view and the unsympathetic view. The sympathetic view, commonly but not unanimously held by civil libertarians and homeless advocates, is that panhandling is essential to destitute people's survival, and should not be regulated by police.8 Some even view panhandling as a poignant expression of the plight of the needy, and an opportunity for the more fortunate to help.9 The unsympathetic view is that panhandling is a blight that contributes to further community disorder and crime, as well as to panhandlers' degradation and deterioration as their underlying problems go unaddressed.10 Those holding this view believe panhandling should be heavily regulated by police.

People's opinions about panhandling are rooted in deeply held beliefs about individual liberty, public order and social responsibility. Their opinions are also shaped by their actual exposure to panhandling—the more people are panhandled, the less sympathetic they are toward panhandlers.11 While begging is discouraged on most philosophical grounds and by most major religions, many people feel torn about whether to give money to panhandlers.12 Some people tolerate all sorts of street disorder, while others are genuinely frightened by it. This tension between opposing viewpoints will undoubtedly always exist. This guide takes a more neutral stance: without passing judgment on the degree of sympathy owed to panhandlers, it recognizes that police will always be under some pressure to control panhandling, and that there are effective and fair ways to do so.

Related Problems

Panhandling and its variants are only one form of disorderly street conduct and street crime about which police are concerned. Other forms—not directly addressed in this guide—include:

- Disorderly conduct of day laborers

- Disorderly conduct of public inebriates (e.g., public intoxication, public drinking, public urination and defecation, harassment, intimidation, and passing out in public places)

- Disorderly conduct of transients/homeless (e.g., public camping, public urination and defecation, and sleeping on sidewalks and benches, and in public libraries)

- Disorderly youth in public places

- Harassment (usually sexual) of female pedestrians

- Pickpocketing

- Purse snatchings

- Robbery at automated teller machines (ATMs)

- Trash picking (for food or to salvage aluminum cans and bottles)

- Unlicensed street entertainment†

- Unlicensed street vending (also referred to as illegal peddling).

Some of these other forms of disorderly street conduct may also be attributable to panhandlers, but this is not necessarily so. These problems overlap in various ways, and a local analysis of them will be necessary to understand how they do.

Factors Contributing to Panhandling

Understanding the factors that contribute to your panhandling problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

Whether Panhandling Intimidates Passersby

Panhandling intimidates some people, even causing some to avoid areas where they believe they will be panhandled.13 One-third of San Franciscans surveyed said they gave money to panhandlers because they felt pressured, and avoided certain areas because of panhandling; nearly 40 percent expressed concern for their safety around panhandlers.14 But most studies conclude that intentional aggressive panhandling is rare, largely because panhandlers realize that using aggression reduces their income, and is more likely to get them arrested or otherwise draw police attention to them.15

Whether panhandling intimidates passersby depends, of course, on how aggressive or menacing the panhandler is, but it also depends on the context in which panhandling occurs. In other words, an act of panhandling in one context might not be intimidating, but the same behavior in a different context might.16 Among the contextual factors that influence how intimidating panhandling is are:

- The time of day (nighttime panhandling is usually more intimidating than daytime panhandling)

- The ease with which people can avoid panhandlers (panhandling is more likely to intimidate motorists stuck in traffic than it is those who can drive away)

- The degree to which people feel especially vulnerable (for example, being panhandled near an ATM makes some people feel more vulnerable to being robbed)

- The presence of other passersby (most people feel safer when there are other people around)

- The physical appearance of the panhandler (panhandlers who appear to be mentally ill, intoxicated or otherwise disoriented are most likely to frighten passersby because their conduct seems particularly unpredictable) 17

- The reputation of the panhandler (panhandlers known to be aggressive or erratic are more intimidating than those not known to be so)

- The characteristics of the person being solicited (the elderly tend to be more intimidated by panhandlers because they are less sure of their ability to defend themselves from attack)

- The number of panhandlers (multiple panhandlers working together are more intimidating than a lone panhandler)

- The volume of panhandling (the more panhandlers present in an area, the more intimidating and bothersome panhandling will seem).

Who the Panhandlers Are

Typically, relatively few panhandlers account for most complaints to police about panhandling.18 The typical profile of a panhandler that emerges from a number of studies is that of an unemployed, unmarried male in his 30s or 40s, with substance abuse problems, few family ties, a high school education, and laborer's skills.19 Some observers have noted that younger people—many of whom are runaways or otherwise transient—are turning to panhandling.20, † A high percentage of panhandlers in U.S. urban areas are African-American.21 Some panhandlers suffer from mental illness, but most do not.22 Many panhandlers have criminal records, but panhandlers are nearly as likely to have been crime victims as offenders.23 Some are transient, but most have been in their community for a long time.24

† In many less-developed countries, children commonly beg to support themselves and their families, a phenomenon less common in the United States and other more highly developed countries.

Contrary to common belief, panhandlers and homeless people are not necessarily one and the same. Many studies have found that only a small percentage of homeless people panhandle, and only a small percentage of panhandlers are homeless.26, ‡

‡ Definitions of homelessness vary, but at a minimum, most studies have found that few panhandlers routinely sleep outdoors at night. See, however, Burke (1998) for evidence that a high percentage of the panhandlers in Leicester, England, have been homeless.

Most studies conclude that panhandlers make rational economic choices—that is, they look to make money in the most efficient way possible.27 Panhandlers develop their "sales pitches," and sometimes compete with one another for the rights to a particular sales pitch.28 Their sales pitches are usually, though not always, fraudulent in some respect. Some panhandlers will admit to passersby that they want money to buy alcohol (hoping candor will win them favor), though few will admit they intend to buy illegal drugs.29 Many panhandlers make it a habit to always be polite and appreciative, even when they are refused. Given the frequent hostility they experience, maintaining their composure can be a remarkable psychological feat.30 Panhandlers usually give some consideration to their physical appearance: they must balance looking needy against looking too offensive or threatening.31

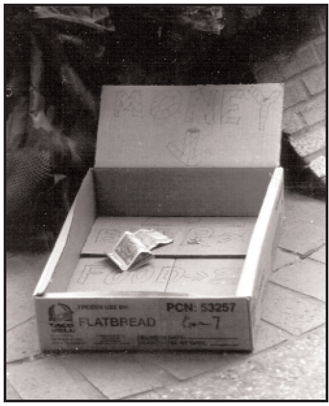

Some panhandlers hope that candor will increase donations. Here, a panhandler's donation box reveals that the money will be spent on beer as well as on food. Credit: Kip Kellogg

Most panhandlers are not interested in regular employment, particularly not minimum-wage labor, which many believe would scarcely be more profitable than panhandling.32 Some panhandlers' refusal to look for regular employment is better explained by their unwillingness or inability to commit to regular work hours, often because of substance abuse problems. Some panhandlers buy food with the money they receive, because they dislike the food served in shelters and soup kitchens.33

Who Gets Panhandled and Who Gives Money to Panhandlers

In some communities, nearly everyone who routinely uses public places has been panhandled.† Many who get panhandled are themselves people of modest means. Wealthy citizens can more readily avoid public places where panhandling occurs, whether consciously, to avoid the nuisances of the street, or merely because their lifestyles do not expose them to public places. Estimates of the percentage of people who report that they give money to panhandlers range from 10 to 60 percent.34 The percentage of college students who do so (between 50 and 60 percent) tends to be higher than that of the general population. There is some evidence that women and minorities tend to give more freely to panhandlers.35 Male-female couples are attractive targets for panhandlers because the male is likely to want to appear compassionate in front of the female.36 Panhandlers more commonly target women than men,37 but some find that lone women are not suitable targets because they are more likely to fear having their purses snatched should they open them to get change.38 Conventioneers and tourists are good targets for panhandlers because they are already psychologically prepared to spend money.39 Diners and grocery shoppers are good targets because dining and grocery shopping remind them of the contrast between their relative wealth and panhandlers' apparent poverty. Regular panhandlers try to cultivate regular donors; some even become acquaintances, if not friends.

† Ninety percent of San Franciscans surveyed reported having been panhandled within the past year (Kelling and Coles 1996).

Where and When Panhandling Commonly Occurs

Panhandlers need to go where the money is. In other words, they need to panhandle in communities and specific locations where the opportunities to collect money are best—where there are a lot of pedestrians or motorists, especially those who are most likely to have money and to give it.40 Panhandling is more common in communities that provide a high level of social services to the needy, because the same citizens who support social services are also likely to give money directly to panhandlers; panhandlers are drawn to communities where both free social services and generous passersby are plentiful.41 With respect to specific locations, panhandlers prefer to panhandle where passersby cannot readily avoid them, although doing so can make passersby feel more intimidated.42

Among the more common, specific panhandling locations are the following:

- Near ATMs, parking meters and telephone booths (because ATM users, motorists and callers are less likely to say they do not have any money to give)

- Near building entrances/exits and public restrooms with a lot of pedestrian traffic

- On or near college campuses (because students tend to be more sympathetic toward panhandlers)

- Near subway, train and bus station entrances/exits (because of high pedestrian traffic, and because public transportation users are likely to be carrying cash to buy tickets or tokens)

- On buses and subway trains (because riders are a "captive audience")

- Near places that provide panhandlers with shade and shelter from bad weather (such as doorways, alcoves and alleys in commercial districts)

- In front of convenience stores, restaurants and grocery stores (because panhandlers' claims to be buying food or necessities for them or their children seem more plausible, and because shoppers and diners often feel especially fortunate and generous)

- At gas stations (because panhandlers' claims that they need money for gas or to repair their vehicle seem more plausible)

- At freeway exits/entrances (because motorists will be stopped or traveling slowly enough to be able to give money)

- On crowded sidewalks (because it is easier for panhandlers to blend in with the crowd should the police appear)

- At intersections with traffic signals (because motorists will be stopped)

- Near liquor stores and drug markets (so the panhandlers do not have to travel far to buy alcohol or drugs).43

There are typically daily, weekly, monthly, and seasonal patterns to panhandling; that is, panhandling levels often follow fairly predictable cycles, which vary from community to community. For example, panhandling may increase during winter months in warm-climate communities as transients migrate there from cold-weather regions. Panhandling levels often drop around the dates government benefits are distributed, because those panhandlers who receive benefits have the money they need. Once that money runs out, they resume panhandling.44 Panhandling on or near college campuses often follows the cycles of students' going to and coming from classes.45 There are usually daily lulls in panhandling when those panhandlers who are chronic inebriates or drug addicts go off to drink or take drugs. Regular panhandlers keep fairly routine schedules, typically panhandling for four to six hours a day.46

Economics of Panhandling

Most evidence confirms that panhandling is not lucrative, although some panhandlers clearly are able to subsist on a combination of panhandling money, government benefits, private charity, and money from odd jobs such as selling scavenged materials or plasma.47 How much money a panhandler can make varies depending on his or her skill and personal appeal, as well as on the area in which he or she solicits. Estimates vary from a couple of dollars (U.S.) a day on the low end, to $20 to $50 a day in the mid-range, to about $300 a day on the high end.48 Women—especially those who have children with them—and panhandlers who appear to be disabled tend to receive more money.49 For this reason, some panhandlers pretend to be disabled and/or war veterans. Others use pets as a means of evoking sympathy from passersby. Panhandlers' regular donors can account for up to half their receipts.50

Panhandlers spend much of their money on alcohol, drugs and tobacco, although some money does go toward food, transportation and toiletries.51 Panhandlers rarely save any money, partly because they risk having it stolen, and partly because their primary purpose is to immediately buy alcohol or drugs.52

Economic, Social and Legal Factors That Influence Panhandling Levels

Broad economic, social and legal factors influence the overall level of panhandling, as well as community tolerance of it.53 Tolerance levels appear to have declined significantly during the 1990s, at least in the United States, leading to increased pressure on police to control panhandling.

The state of the economy, at the local, regional and even national level, affects how much panhandling occurs. As the economy declines, panhandling increases. As government benefit programs become more restrictive, panhandling increases.54 At least as important as economic factors, if not more so, are social factors. The stronger the social bonds and social network on which indigent people can rely for emotional and financial support, the less likely they are to panhandle.55 Thus, the weakening of social bonds throughout society affects the indigent most negatively. As substance abuse levels rise in society, as, for example, during the crack epidemic, so too do panhandling levels. As the skid rows in urban centers are redeveloped, the indigent people who live there move to areas where their panhandling is less tolerated. As people with mental illnesses are increasingly released into the community, often without adequate follow-up care, panhandling also increases. Where there are inadequate detoxification and substance-abuse treatment facilities, panhandling is high.56 As courts strike down laws that authorize police to regulate public disorder, and as police are less inclined to enforce such laws, panhandling flourishes.57 Arrest and incarceration rates may also affect panhandling levels: convicted offenders often have difficulty getting jobs after release, and some inevitably turn to panhandling.58

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Panhandling

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.